Defra Food Consultation 2022

Following the consultation of the UK Government’s Buying Standards for Food and Catering, Lee Sheppard, Director of Corporate Affairs and Policy for apetito, the leading meals provider into the Health and Social care sectors, says that the current thinking is flawed and should be challenged, as it risks failing to meet its objectives, with negative impacts for sustainability, health outcomes, and cost.

“The challenge here is that Government has focused on “what looks good,” without sufficiently factoring in “what does good.” Despite widespread consultation the proposed GBS risks taking us backwards. I see the key challenges as below:

Using “local” as a proxy for sustainable

Defra seems to view the UK food system as somewhat comparable to a “farm shop” type arrangement – where the public sector (as well as us all as individuals) go merrily along (in their electric delivery vehicles no doubt) and pick up their bunch of locally grown carrots from the local farm shop.

Whilst this plays to the media rhetoric of “sustainable,” not only is it completely impractical, but there is widespread evidence that Defra is focusing on the wrong issue. The food we consume has a far, far greater impact on carbon footprint than food miles.

This was reflected in The National Food Strategy (The Dimbleby Report), which reported that the transport of food – the famous ‘food mile’ actually accounts for only 13% of the food system’s total carbon footprint. There are other reports, including our own analysis, that suggest it may be even lower.

In addition, a European study in 2018 showed that whilst food transport was ONLY responsible for 6% of emissions, the production of dairy, meat, and egg products account for 83% (1). It’s typical for food businesses to see over 2/3 of its carbon footprint arise from its ingredients alone.

A further study published in Environmental Science & Technology, Christopher Weber and Scott Matthews (2008) investigated the relative climate impact of food miles and food choices in households in the US. Their analysis showed that substituting less than one day per week’ worth of calories from beef and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or a plant-based alternative reduces GHG emissions more than buying all your food from local sources (2).

In fact - and I don’t pretend that this is always the case - but for the wrong ingredient, producing locally can actually increase emissions and cost. There are many examples of studies which show that importing often has a lower footprint. Hospido et al. (2009) estimates that importing Spanish lettuce to the UK during winter months results in three to eight times lower emissions than producing it locally.

The same applies for other foods: tomatoes produced in greenhouses in Sweden used 10 times as much energy as importing tomatoes from Southern Europe where they were in-season (3).

A requirement that 50% of food spend be on locally produced food

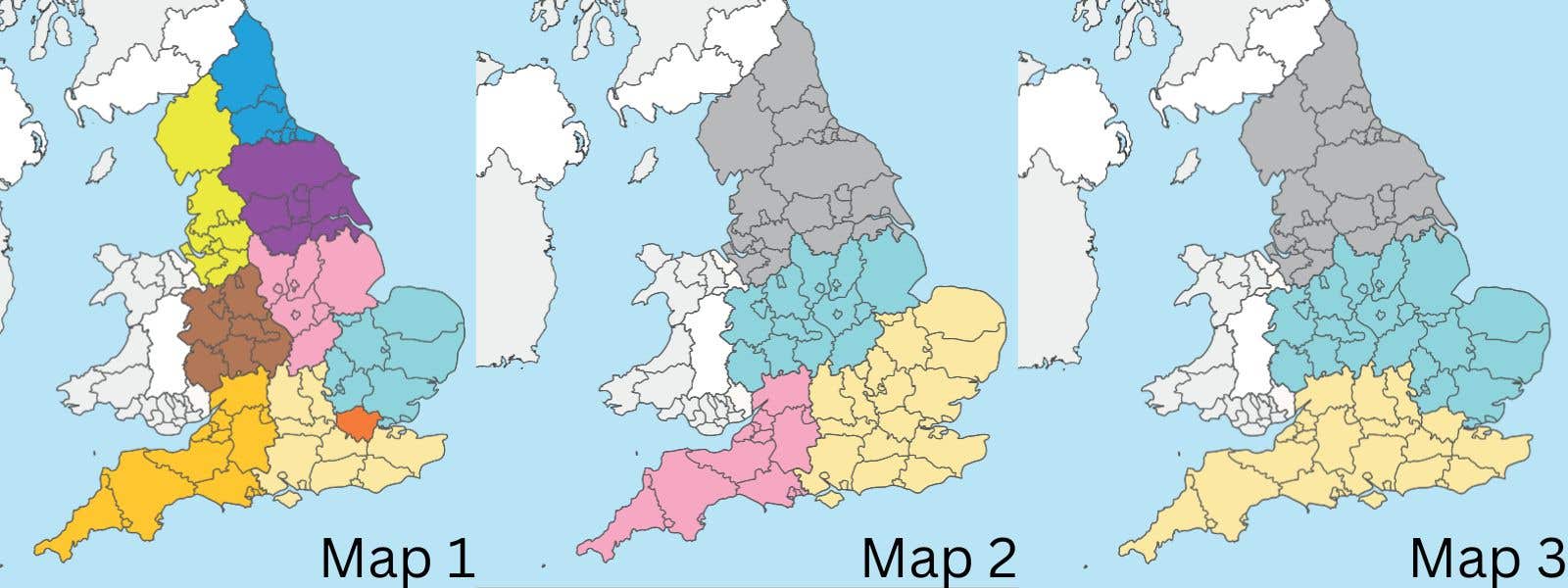

Defra’s stated preference for the definition of local is ‘produced/grown/caught/ within the same region as it is consumed. To support this, it has created “options” of what local maps may look like.

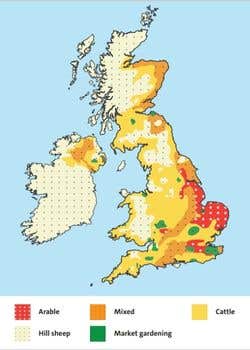

The impossibility of this comes to light when one looks to overlay where the UK farming regions actually are:

As you can see there is no correlation between these which leaves the question – “Did Defra consider how and where the UK farms?” Is it practicable or even possible for peas and potatoes to be harvested locally to each NHS Trust?

The East of the UK dominates our arable crop production – are we now going to replicate this in the SW, NW, SE? Is this even agriculturally possible and at what cost?

Can fish be sourced “locally” as Defra would require, despite the fact that both the Marine Conservation Society and Marine Stewardship Council (the real fish sustainability experts), don’t share this view. Does Defra really want to encourage us to stop eating varieties of Prawns and Tuna despite them being accepted as sustainable, simply because they are not “locally caught” anywhere in the UK?

The proposal risks generating more food insecurity and more food waste – if customers are not allowed to source from suppliers with available products (because they are grown “outside of their local area”) then there will be farmers with excess production that they have no demand for, and customers in other areas with demand for product - with no-one able to supply! This will be a real, but unintended consequence, of a ill-thought through policy to keep focus on the issue of food miles that has been widely discredited, instead of looking to drive real improvement in public procurement catering standards.

Positioning “local” as a proxy for health.

This assumption has been made by Defra without any evidence that associates local products with greater health benefits.

Indeed, many larger food manufacturers invest heavily in research and development, generating specialist nutrition solutions for many dietary needs across the public sector. One supplier cites that circa 20% of meals it provides to the NHS are for specific dietary needs.

Can we really meet all religious and cultural food demands on a local footprint - are there enough specialist suppliers across the UK to replicate this activity?

We risk compromising investment in food innovation if suppliers do not have the ability to market these dishes across a larger national footprint.

Failing to Tackle Net Zero

Whilst there is some commentary around Net Zero, the subject is noticeable in the complete lack of any standards relating to it. In particular, the standards are silent on the role of the food we eat on climate change, despite the fact that The Government’s Climate Change Committee has said we must reduce the amount of meat we eat by 20–50% in order for the UK to reach net zero by 2050. Why has Defra shied away from this critical topic – another example of focusing on what “looks good”, rather than what “does good.”

Driving Cost into the Public Sector

The net result of this misguided view is that not only will the current approach fail to deliver better outcomes against identified objectives, but it will drive significant costs into the public purse.

I welcomed the UK’s Government new Food Strategy when it was published and the desire to drive up standards.

However, I would encourage the Government to focus on driving real improvement in public procurement catering standards through following the evidence rather than the rhetoric. That way we can enable people to eat for health and cater for a whole range of dietary and cultural needs, both for the nutritionally well and unwell, in line with a more sustainable, cost-effective food system.

It’s time to focus on what “does good” not what “looks good.” Industry is here to help. We urge Defra to listen before it is too late....

Sources:

(1)Sandström, V., Valin, H., Krisztin, T., Havlík, P., Herrero, M., & Kastner, T. (2018). The role of trade in the greenhouse gas footprints of EU diets. Global Food Security, 19, 48-55.

(2)Weber, C. L., & Matthews, H. S. (2008).Food-miles and the relative climate impacts of food choices in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology.

(3)Carlsson-Kanyama, A., Ekström, M. P., & Shanahan, H. (2003).Food and life cycle energy inputs: consequences of diet and ways to increase efficiency.Ecological Economics, 44(2-3), 293-307.

For further information please contact: